Born in New London, Connecticut, in 1795 to a widowed, impoverished, teen-aged mother, Frances Manwaring Caulkins grew up in the household of a farmer who worked as a tanner and shoe-maker. She had scant opportunity for a formal education, and often struggled to support herself, but she used self-education and self-improvement linked with her strong desire to make something of her life to rise above the limitations of her background and upbringing. She succeeded in supporting herself, her siblings, and her widowed mother for fourteen years as a teacher. She not only participated in voluntary associations; she initiated them. She published dozens of poems, numerous newspaper articles, and at least a dozen popular religious tracts. Her most notable achievements were two critically acclaimed histories of Norwich and New London, histories so carefully researched that they are still of value to modern historians.

Born in New London, Connecticut, in 1795 to a widowed, impoverished, teen-aged mother, Frances Manwaring Caulkins grew up in the household of a farmer who worked as a tanner and shoe-maker. She had scant opportunity for a formal education, and often struggled to support herself, but she used self-education and self-improvement linked with her strong desire to make something of her life to rise above the limitations of her background and upbringing. She succeeded in supporting herself, her siblings, and her widowed mother for fourteen years as a teacher. She not only participated in voluntary associations; she initiated them. She published dozens of poems, numerous newspaper articles, and at least a dozen popular religious tracts. Her most notable achievements were two critically acclaimed histories of Norwich and New London, histories so carefully researched that they are still of value to modern historians.

Caulkins’s formal education, beyond reading and writing, did not begin until she was eleven, by which time she had read The Iliad and The Odyssey in English translation and had begun to study Latin. She had also already read many of the English writers of the 17th and 18th centuries. A few years later, Caulkins was able to study at an academy in Norwich under the direction of two rather extraordinary Norwich teenagers, Lydia Huntley and Nancy Hyde. Both girls had suffered through the education prescribed for genteel young women, and they were determined to provide a different kind of education for young women in their school. They opened their school in Norwich in the fall of 1811. Frances was one of their students, remaining there through the spring of 1812. Though the school did offer the traditional fine arts, Huntley and Hyde were more interested in the challenging academic curriculum they themselves had longed for. They provided daily lessons in ancient and modern geography and in natural and moral philosophy. Students studied history four days each week, and all the girls kept daily journals in which they wrote regular compositions on a wide range of topics. Some of the girls also wrote poetry in their journals; this may be where Caulkins developed her poetic interests and talents. Grammar, logic, arithmetic, and penmanship took precedence over Bible reading, prayer, recitation, and spelling. Hyde was clear about the school’s educational goals, writing: “Usefulness should be the result of education.” Caulkins valued her time with Huntley and Hyde, later writing that they taught her to love learning for its own sake and to treat her work as a pleasure.

When Nancy Hyde died in 1816, Huntley raised money to publish a collection of Hyde’s writings, including prose, poetry, and journal entries. Working both as editor and publisher of the book, Huntley asked Frances to write a memorial to Hyde. “Lines to the Memory of Miss Nancy Maria Hyde,” was a maudlin poem, typical of much poetry in that era. A former neighbor of Nancy Hyde’s read the tribute that Frances had written and sent Frances a letter in which he encouraged her to keep writing, because her skill had made Hyde “bloom again.”

Any aspirations to be a writer had to be put on hold when Caulkins’s stepfather, Philomen Haven, died in 1819 leaving his widow with three children under the age of 12 and no source of income. Frances supported her mother, half-siblings, and her elder sister Pamela for the next fourteen years by operating young ladies’ schools in Norwich, then New London, then Norwich again. She closed the last school rather abruptly in 1834, although it had been doing well. Possibly this was partly out of fear that her anti-slavery activities would lead to action against her school. These activities included a poem entitled “An Original Hymn to be Sung on the Fourth of July, 1834,” that castigated Northern society, Norwich industrialists, and thus Norwich citizens as well, for celebrating their own birthright of freedom and liberty on the Fourth of July because America had built its freedom on the oppression of enslaved blacks.

After taking a year to travel, Caulkins moved to New York City to live with a family of cousins whose mother had died. While there, Caulkins became a prolific writer for the American Tract Society. The Society printed over one million copies of the second tract that she wrote, a pious piece she titled The Pequot of One Hundred Years. Many of her tracts had press runs of several hundred thousand copies, and the Society translated a number of them into foreign languages for the use of its missionaries abroad.

In 1842 Caulkins moved back to New London, taking up residence in the home of her half-brother Henry Haven, helping to care for his children and her aging mother. Perhaps the most important reason that Caulkins moved back to Connecticut was that Haven was in a position to provide her with the security she craved and the leisure to continue her writing. No longer faced with the need to write religious tracts to support herself, Caulkins was able to turn her attention to writing the history of her native towns. She had been meticulously compiling historical and genealogical information for years, to the point where by 1845 she was able to publish her History of Norwich, Connecticut: From its Possession by the Indians to the Year 1845. A greatly expanded edition was published in 1874.

The book was a great success, and Caulkins became known in wider circles than Eastern Connecticut. In 1849 she was elected corresponding member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Society’s first female member, and only one until 1966.

Caulkins’s second history, The History of New London, Connecticut, From the First Survey of the Coast, to 1852, was published in 1852. It is still the best reference for pre-Civil War New London. An update to 1860 was added in later printings.

As if she were not busy enough, in 1845 Caulkins, along with her sister-in-law and the wife of her brother’s business partner, initiated the New London Ladies’ Seamen’s Friend Society. She served as the secretary of the organization from its founding until her death in 1869, recording the wide-ranging projects of the Society, demonstrating the ability of “mere” women to alleviate the suffering of honest mariners and to distinguish between the honest supplicants and the humbugs.

Toward the end of her life, Caulkins apparently came to believe that she had accomplished little of note. She collected articles that praised mothers as the “uncrowned queens” of society and seemed to ascribe to Lydia (Huntley) Sigourney’s opinion that only married women with children would leave a lasting legacy, noted and recorded by their families. In his funeral memorial to Frances, half-brother Henry detailed her triumphs but noted that she had died feeling she was a failure. Little did Frances Caulkins know that her lively and vivid histories would live long after the memories of her friends and families had faded.

Nancy Steenburg

Born in New London in 1678, Joshua Hempstead (the second) kept a diary from 1711 until his death in 1758. Hempstead was a Justice of the Peace, shipbuilder, and cartographer, who plied his trades in New London and surrounding area. Today, the diary is one of the best sources of information about the people of colonial New London and their activities. The third edition transcription of the Joshua Hempstead Diary contains additional material, a forward by Patricia Schaefer, and a more comprehensive index.

Born in New London in 1678, Joshua Hempstead (the second) kept a diary from 1711 until his death in 1758. Hempstead was a Justice of the Peace, shipbuilder, and cartographer, who plied his trades in New London and surrounding area. Today, the diary is one of the best sources of information about the people of colonial New London and their activities. The third edition transcription of the Joshua Hempstead Diary contains additional material, a forward by Patricia Schaefer, and a more comprehensive index.

Reports to the Executive Director.

The NLCHS seeks a detail-oriented and forward-thinking individual to join a team to help establish and grow the organization’s Development Department. The Development Manager will assist the Executive Director in grant writing and research. Additionally the Development Manager will assist in increasing membership and soliciting donors to support the institution. The position offers flexible work hours, and a hybrid work environment. Currently, the position is grant funded for one year. The successful candidate will increase income to support a permanent full time salaried position. Applicants should submit a CV or resume and, a cover letter via email to executivedirector@nlchs.org. Please include “Development Manager” in the subject line.

Bachelor’s degree a plus

Proficiency in Google applications

Two or more years of related professional experience in development at a not-for-profit organization

Strong technology skills and general computer literacy

Excellent verbal and written communication skills

Strong analytical and problems solving skills

Ability to meet competing deadlines on time, while working independently and exercising thoughtful prioritization

Excellent organizational skills and attention to detail

As you enter Shaw Mansion you may see a plaque next to the door stating that the Shaw Mansion served as the U.S. Naval Office during the American Revolution. The meaning of this simple statement is a bit complex.

The Continental Navy was officially established on October 13, 1775. However this did not mean the country would be building ships which flew the a United States flag. Any new navy needs regulations and clear chain of command. The arduous task of composing the regulations fell Congress. Esek Hopkins was appointed to command the Continental Fleet consisting of six ships, a mere fraction of the overall navy of the Revolution. When the Continental Navy needed more ships, they asked governors of various states to loan vessels from the state navies. The he U. S. Naval Office in New London had little to do with the Continental Navy.

On March 23, 1776, Congress approved a maritime act allowing for general reprisal and the use of letters of marque against British vessels. The legislation was the first step to instituting the practice of privateering in the revolutionary war. “Resolved that all Ships &c. belonging to any Inhabitants of Great Britain as aforesaid, which shall be taken by any Vessel of War, fitted out by and at the Expense of any of the United Colonies, shall be deemed forfeited, and divided, after deducting and paying the Wages of Seamen and Mariners as aforesaid, in such manner and proportions as the Assembly or Convention of such Colony shall direct.” British ships were now legally available to privateers as prizes for the taking.

Privateering is often erroneously defined as legalized piracy. However, that definition is quite inaccurate. There are some significant differences between pirates and privateers. Pirates were individuals who chose to leave institutionalized maritime activity to be free of laws and regulations. Their activity at sea was often democratic. They elected their captain and voted on their destination. The captain was only allowed to be in command during battle. That notion is quite different from traditional ships where the captain is the sole authority aboard the vessel. When a ship was taken by pirates, the money associated with that capture was divided by the agreement of the crew. Conversely, privateers had to obey laws, their course was determined by the ship’s captain or owners, captures were determined legal through the courts, and prize money awarded was apportioned using strict guidelines authored by Congress.

On April 3rd 1776 Congress issued the articles under which privateers were to sail. Additionally crew conduct was assured by owners posting a surety pound bond with the naval agents. A letter of marque issued by the naval agent was required by anyone who wished to engage in privateering.

A letter of marque is document which provided protections to the privateer, as it declared the privateer was a military combatant. As such the captured privateer was treated as a prisoner of war. Without the letter of marque, the privateer was subject to piracy laws, thus available to be charged and tried for piracy. Prisoners of war enjoyed rights of decent treatment, available for prisoner exchange, and a guaranteed safe return home after a treaty was signed. Pirates were typically hung.

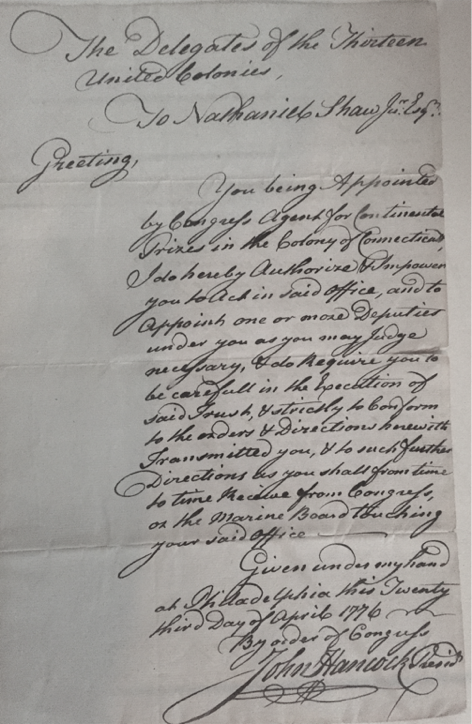

Naval agents were appointed administer the continental navy in each state, but the larges portion of their job involved organizing the privateering effort. The agent’s job was arduous. They were required to keep all the administrative records of all individuals and ships engaged in the activity. Most colonies had agents, in some instances there were two, in the case of Virginia there were none. In Connecticut, Nathaniel Shaw Jr was appointed the Navy Agent on April 17, 1776. Shaw not only served as the agent for the Continental Congress, he also served as agent for the colony of Connecticut. He became the sole administrator for all warships entering and exiting the port of New London.

After a privateer captured an enemy vessel, the process for receiving prize money was lengthy. The law stated that any captured ship was to be brought to the closest colonial port. Once there the ship was inventoried and written accounts of her capture were collected. The inventories and accounts were then sent a state county court to be reviewed, and the court declared whether the capture was legal. Then the courts awarded prize money. Everyone involved in the capture, crewmen, officers, captain, naval agent, investors, state government, and the Colonial government was allocated a percentage of the money earned from every sale of captured ships.

There are different estimates concerning number of ships taken by privateers and brought into the ports of Connecticut. Several sources record that 500 ships were taken, while others state 600 ships. The confusion for the numbers is two fold. What constituted an official prize coupled with the records destroyed when Arnold burned New London in 1781. The privateering effort of New London, for all of the colonies was significant at least in an economic standpoint. British shipping to the colonies became quite hazardous, and the insurance rates for such voyages rose to be prohibitive. Privateering during the Revolution was quite lucrative. Men motivated by the prospect of a 150% pay increase signed aboard privateers taking advantage of the opportunity to profit. That opportunity was responsible for the largest fleet of American ships sailing during the Revolution.