The Second Largest Whaling Port IN THE WORLD in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century

New Londoners have always depended upon their excellent harbor and their connection to the sea for their livelihood, so it should come as no surprise that they would seek to meet the market demand and exploit the world’s largest mammals for their oil.

At the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century the development of steam engines and machinery for spinning and weaving textiles created an industrial revolution. Those machines also created a demand for fine lubricants. The oil from whales, especially sperm whales, was the finest, and New London whalemen increasingly sought to return from distant voyages with ships full of oil to sell. By the middle of the nineteenth century New London had become the second largest whaling port in the world; a total of 257 ships embarked on over 1100 separate whaling voyages between 1718 and 1908.

New London vessels holds records for the longest voyage, the most successful voyage, the first steam powered whaling vessel, and the largest whaleship. New London captains were some of the first to go whaling and sealing in remote areas of the Western Arctic and Indian Oceans.

Oil From Whales

Oil taken from Sperm Whales is the finest natural lubricant in the world. Unlike most animal fats, sperm oil is classified as liquid paraffin. It is very stable, does not degrade and become sticky, and burns very cleanly and very brightly with no soot or smoke. It has been used to lubricate the most delicate of instruments and in a number of industrial applications.

Because of its exceptional burning characteristics, the government was one of the largest purchasers of sperm oil during the nineteenth century to use in coastal lighthouses – where the safety of shipping and passengers depended upon avoiding dangerous shoals, rocks and islands. Until the selling of whale products became illegal in 1972, sperm oil was used in car transmissions, to lubricate clocks and sewing machines, and for delicate machinery on submarines and satellites.

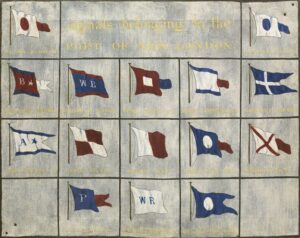

A Key to the House Flags of the Whaling Firms of New London, 1846

The large capital investment involved in putting together the ship and outfit for a whaling voyage was managed by agents who were generally the primary owners of the ships. Not wanting to put “all of their eggs in one basket,” whaling merchants were more likely to own several partial shares of a number of vessels rather than being the sole owner of one vessel.

By 1846, New London had more whaling ships on the seas than any other port other than New Bedford, Massachusetts. The fifteen firms operating in New London in that year are listed with their house flag.

The house flags were important communicators. Flying most of the time at the peak of the main or foresail, the flags could be seen at a great distance and the ship could be identified even from far away. Captains would sometimes move the signal to different locations on the ship to communicate with their crews who were out pursuing whales in smaller whaleboats.

Just About Everyone’s Livelihood Depended upon Whaling

At the middle of the nineteenth century New London’s economy was driven by the effort required to bring large amounts of oil processed from the blubber of whales to shore. The city directory of the time lists ship builders, sail makers, coopers – to make barrels to hold the oil and the provisions, and bakers – to bake the ships’ bread. Rope makers, block makers, and smiths are some of the most obvious related businesses. But there were also photographers, cigar merchants, ready-made clothing stores, and lots of saloons all catering to men about to head out for long journeys.

The men who owned the ships often also had businesses that supplied the materials that were required for a voyage. They owned the banks and railroads, building supplies companies and hardware stores, and they ran the town.

The wives of seamen made clothing to sell and took in laundry and did other handwork as they cared for their families and waited for their sailors to return. The wives of captains and merchants organized the Lewis Female Cent Society to support the vulnerable families left behind, and the Seamen’s Friend Society to attempt to provide alternatives to the saloons.